Image: Photo by Lucca Belliboni on Unsplash

Image: Photo by Lucca Belliboni on Unsplash

Bringing various perspectives into dialogue with each other, this curation foregrounds the polyphonous voices and experiences of the many South Asian residents of the Gulf.

While this curation aims to celebrate and foreground South Asian residents in the Gulf, it is equally important that it acknowledges the structural disadvantages and injustices endured by many of these residents. Consequently, some of the works in this curation will feature sensitive content. Some content warnings will be visible in the 'Public Notes' sections of the respective works.

The terms expat and migrant appear in popular and scholarly works within the collection. As critics have noted however, the ways in which these terms are utilized contribute to the persistence of the division between expatriates and migrants. The former tends to be used in reference to those coming from privileged countries in the Global North while the latter, to those from the Global South. In their work on Western Work and Intimacy: Postcolonial Hierarchies in the Gulf, Renard and Kuntz state that these terms "naturalize Western and white privileges by making them invisible" while also presupposing a "homogenous perception of migrants as opposed to expatriates". Neha Vora has suggested that the use of the term 'resident' can help move beyond these dichotomies while bringing to attention the longstanding influence of South Asians in the Gulf. In light of this, I have amended the title of my curation from 'South Asian migrants' to 'South Asian residents', in hopes that it better reflects the intentions of my curation.

This music video by Sarathy Korwar is titled 'Pravasis' and is part of his album More Arriving. The term 'Pravasis' has its roots in Sanskrit and is used in both Hindi and Malayalam, roughly translating into 'a person who changes location', or 'migrant'.

The lyrics to this video are based on Temporary People, an award winning and genre-defying collection written by Deepak Unnikrishnan, based on the lives of migrant workers residing in the Gulf.

A few chapters in Unnikrishnan's collection feature page long lists of the various labels assigned to these migrant workers. These lists, like the one featured in the video, draw attention to how the identities of the South Asian residents of the Gulf are often predetermined, contained and controlled by the labels assigned to them. Appropriating these labels through their own voices and writing, Unnikrishnan and Korwar both reclaim and challenge the limits of such terms.

South Asian-Gulf influencers on social media platforms like Youtube, Instagram and TikTok have grown increasingly popular in recent years. Skits, parodies and other comedic videos in particular gather a lot of traction. In an article on LSE blogs, Nele Lenze suggests that these comedic videos become a site of dissent, allowing creators to speak back to stereotypes and voice injustices through the lens of humor. Nadeen Dakkak has similarly suggested that comedic video representations of migrant workers in the Gulf can function as counter-narratives to stereotypes of victimhood.

While some of these videos might perpetuate exisiting racial and gendered hierarchies, others, like the one featured above by prominent Gulf-Malayalee Youtuber, Muhammad Akief, use humor to tackle social and cultural issues and dismantle dominant power structures.

Often referred to as the Gulf countries, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) was formed in 1981 and comprises of 6 countries: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The population of most Gulf countries tend to be heavily skewed towards expatriates who outnumber the national population in 4 out of the 6 GCC countries. South Asians in particular form the largest expatriate population in the Gulf, with the South Asian-Gulf migration corridor being one of the largest in the world.

Migration to the Gulf is often understood within the context of the 1970’s oil boom that attracted an enormous influx of migrant labour from South Asian countries. However, South Asian-Gulf migration has an extensive pre-oil history and can be traced to pre-Islamic eras as far back as the 7th century, when Indo-Arab trade was flourishing. Attributing the South Asian presence in the Gulf to the discovery of oil ignores this larger historical context and understands it through the limited lens of economic development.

The texts in the History section of this curation trace the trajectories of Gulf migration both before and after the 1970's oil boom, while these texts and those in other sections also expand beyond economic narratives.

As a middle-class Indian resident of the Gulf, I benefit from specific privileges that have allowed me to access this curatorship and that undoubtedly shape the perspective I bring to this curation. Mindful of this, I have attempted to curate a wide range of resources and bring a variety of South Asian voices into conversation with each other, in ways that sometimes comment on, corroborate and contradict each other.

While I undoubtedly hold a specific position of authority as the curator of this collection, the curation is also a collaborative effort; the final collection is a product of various conversations I've had with and recommendations I've received from different academics and organizations, as well as the generous help and advice I have received from members of Library team.

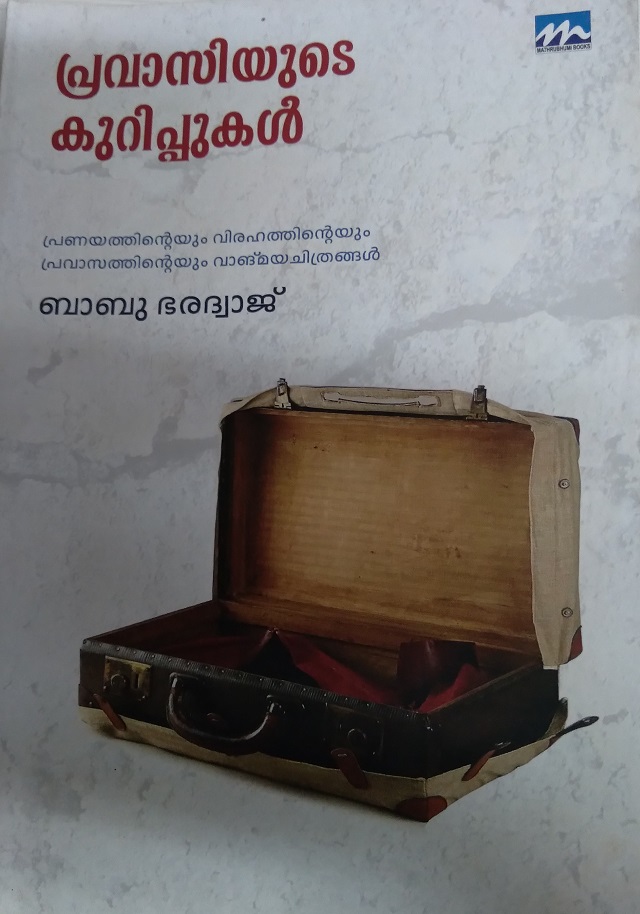

However, amongst other limitations, the library catalogue’s English language bias and the curatorship's budget mean that this curation is inevitably incomplete. Many South Asian language texts, such as Babu Bharadwaj’s Malayalam memoirs, have yet to be translated and so could not be included within this curation. Additionally, the curation features far more academic scholarship about South Asians in the Gulf as compared with first hand accounts and creative outputs like fiction and art. As writers and academics have noted, there is a need for more literature, art and other works which platform the voices of Gulf-South Asians. As such, rather than an all encompassing collection, I position the curation as a simple starting point.

Image: Pravasiyude Kurippukal by Babu Bharadwaj

Although I have chosen to focus on South Asian residents, the Gulf is home to many different migrant communities from across the world. There is both considerable overlap and distinction between the experiences of these different migrant communities and South Asians in the Gulf, but it has been beyond the scope of this curation to address this - although some resources in the collection do draw some of these wider connections. It has not been the intention of the curation to separate or isolate South Asian residents from these broad communities that exist and continue to be formed in the Gulf. Rather, I hoped to create a space that foregrounds South Asian voices and experiences, which continue to be underrepresented or only made selectively visible, both on a national and global scale.

Hi! I’m Rachel, a third-year English and Related Literature student. I’m particularly interested in migrant literature and decolonial practice within academic spaces.

Even though I grew up in the UAE, it took a long time for me to even think to search for, much less find, art and scholarship about South Asians in the Gulf. But when I did, seeing myself reflected in those narratives was incredibly important to me. I hope this collection will make it a little easier for others like me who have grown up or reside in the Gulf, to find works that reflect their lives and the lives they have encountered. And for those who haven’t, I hope this curation resonates with global issues of migration, citizenship and belonging, while also filling in gaps in understanding about the Gulf and the South Asian diasporic communities it has long been home to.

As recent world events have demonstrated, laws around citizenship and national borders dictate who gets to belong to or reside in a place, often at great cost to human life. While this curation focuses on the specific topic of South Asians in the Gulf, the themes of citizenship, belonging and migration it deals with are incredibly relevant to the current moment. As both historically established communities and legal non-citizens, instances of South Asian migrant homemaking in the Gulf presented in this collection offer new ways of thinking about borders, nations and diasporas.

Ahmed Kanna, Amélie Le Renard, and Neha Vora speak about their book Beyond Exception: New Interpretations of the Arabian Peninsula. They ask "What would not only Middle East studies, but studies of postcolonial societies and global capitalism in other parts of the world look like if the Arabian Peninsula was central rather than peripheral or exceptional to ongoing sociohistorical processes and representational practices?".

Photography is one of the most popular mediums through which the Gulf has been represented. On one hand there are the drone captured, birds-eye view images of the many urban spectacles the Gulf has come to be synonymous with: record breaking skyscrapers, man-made islands, elaborate skylines. On the other hand, photographs in news articles and popular media depict brown bodies, often crowded together in public spaces. Commenting on this tension, two NYUAD students, Lubnah Ansari and Nandini Kochar, in their article about a photography exhibition on Mina Zayed ask, "what is the line between preserving the histories and lived experiences of Mina Zayed and tokenizing the lives and labor of those who inhabit it?".

Image: Photo by Ryan Miglinczy. Unsplash.

The fetishization of brown bodies, and particularly those of low wage migrant workers raise questions about ethics of consent and the rights of those being photographed: what sorts of stories are the photographs being used to tell? And did those being photographed consent to them? This curation has tried to mindful of the images and photo-essays it features, but the question of consent remains a pertinent and complex one. As Kochar, a photographer herself, has observed, photographers, viewers and subjects often occupy intersecting positions of privilege and vulnerability. When looking through the photographs in this collection, this is something to be attentive to.

As legal non-citizens, South Asians in the Gulf are repatriated upon death. This podcast by Kerning Cultures reveals stories about the families who’ve had to go through the experience, and the group of volunteers who help repatriate the bodies of residents after they’ve died in the UAE.

Visit the See Yourself on the Shelf page to find out more about our student library curator work.

If you have any questions regarding 'In/visible Lives: On the South Asian Residents of the Gulf' please contact the library at lib-enquiry@york.ac.uk

'See Yourself on the Shelf' used with permission from the University of Kent.

Background Image: Aleksandr, stock.adobe.com.